/ Chiang Mai, Thailand /

/ Story: Phattaraphon / English version: Bob Pitakwong /

/ Photographs: Nantiya /

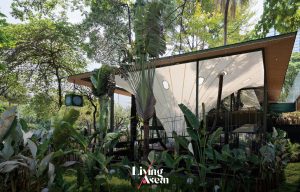

A hotel chain widely recognized in Chiang Mai’s Mae Rim District for the past 15 years has opened a new branch in Muang District in what is seen as a major expansion of luxury, comfort and style. Proud Phu Fah Muang Chiang Mai advocates living next door to nature while showcasing an intriguing combination of modern design with rich culture and beautiful traditional crafts. Its design concept keeps firmly to the belief that being in nature provides deep relaxation. And the result of all this is a resort hotel that’s environmentally conscious, plus it’s tailored to the needs of specialized segments of the market.

Needless to say, the hotel landscape is out of this world. Like taking a spellbinding journey into the woods, Proud Phu Fah Chiang Mai is a perfect escape away from the crowds, where the air is filled with the continuous murmuring sound of water flowing and leaves rustling in the trees creating detailed mental images of the beautiful northern landscape.

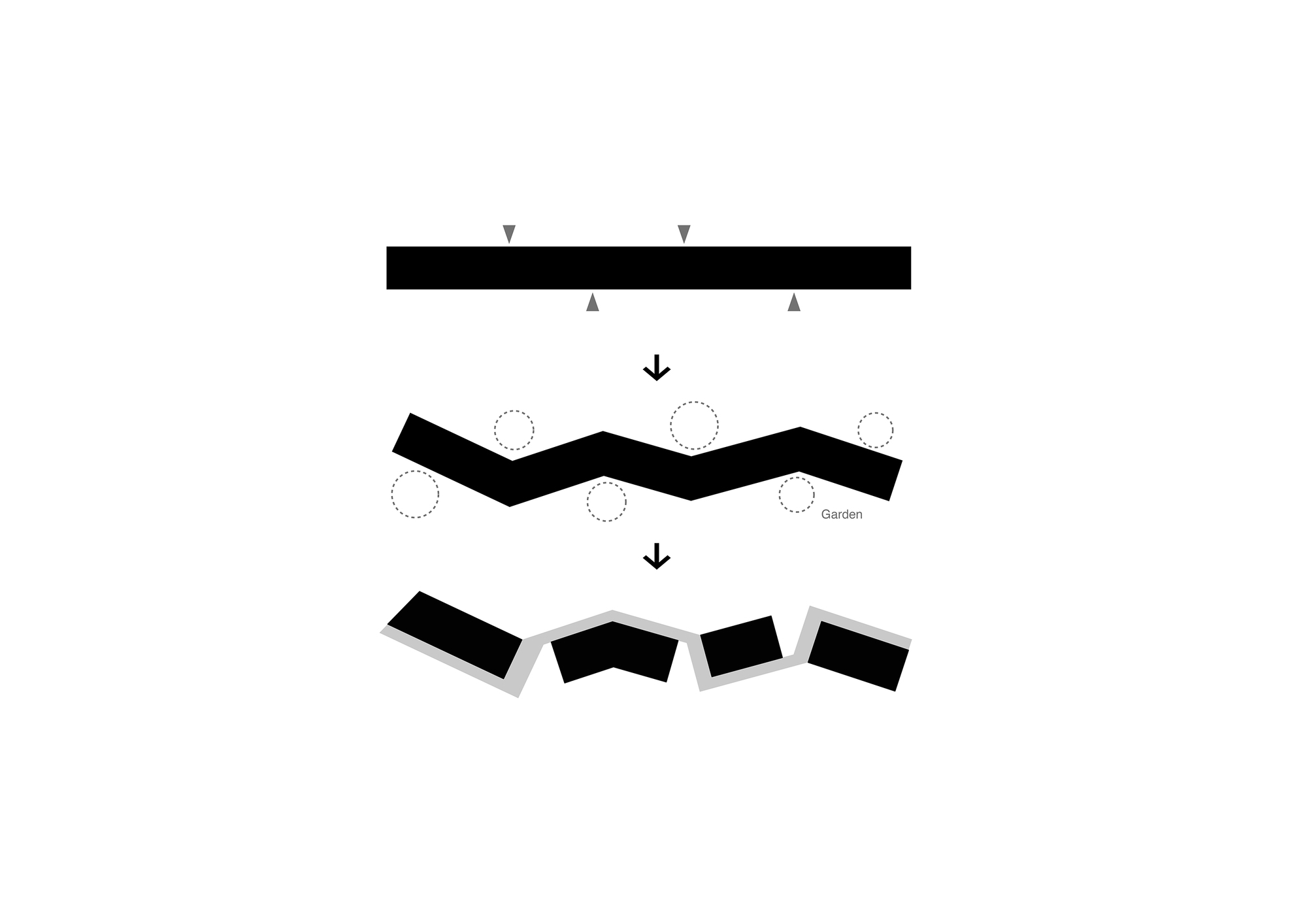

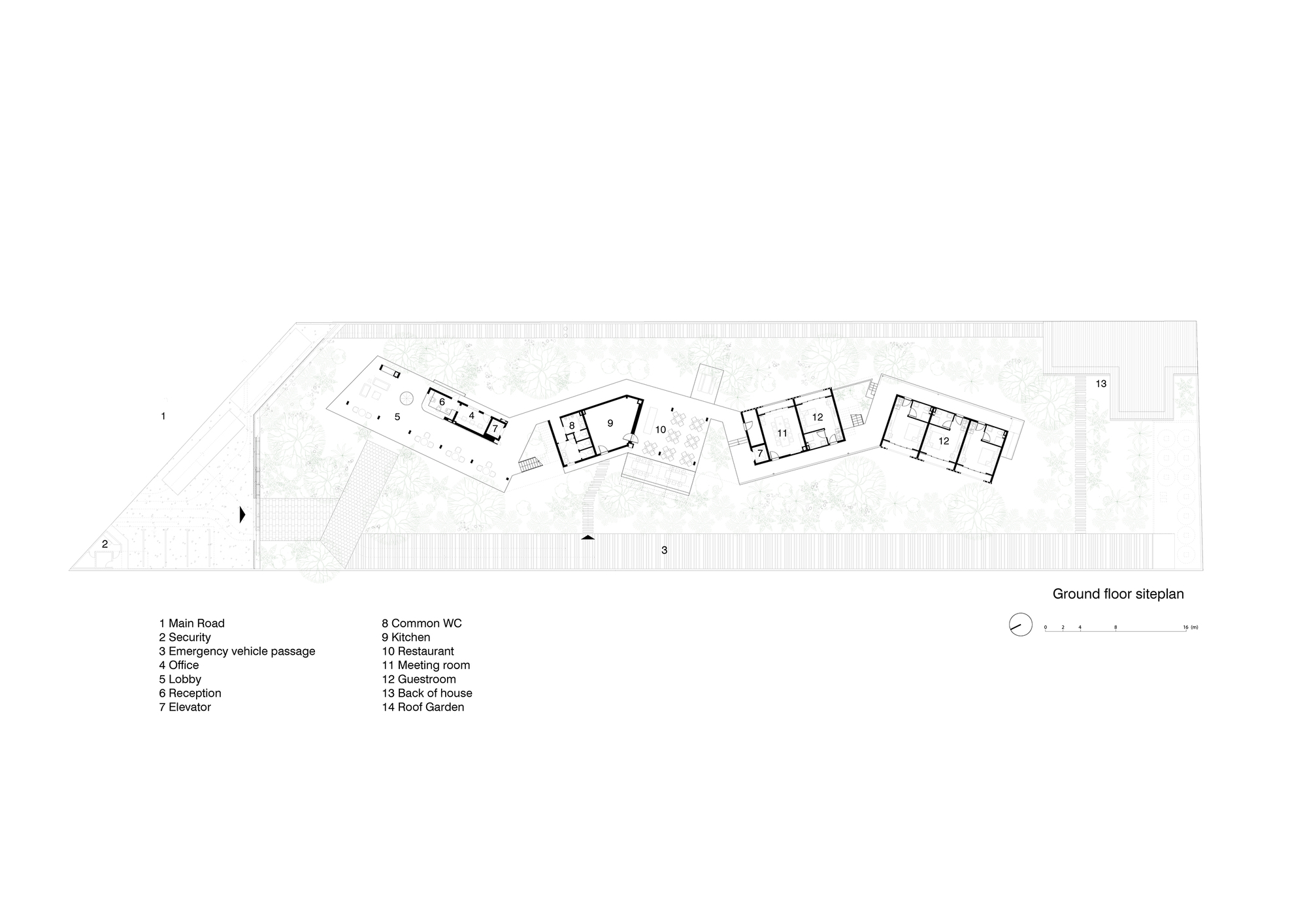

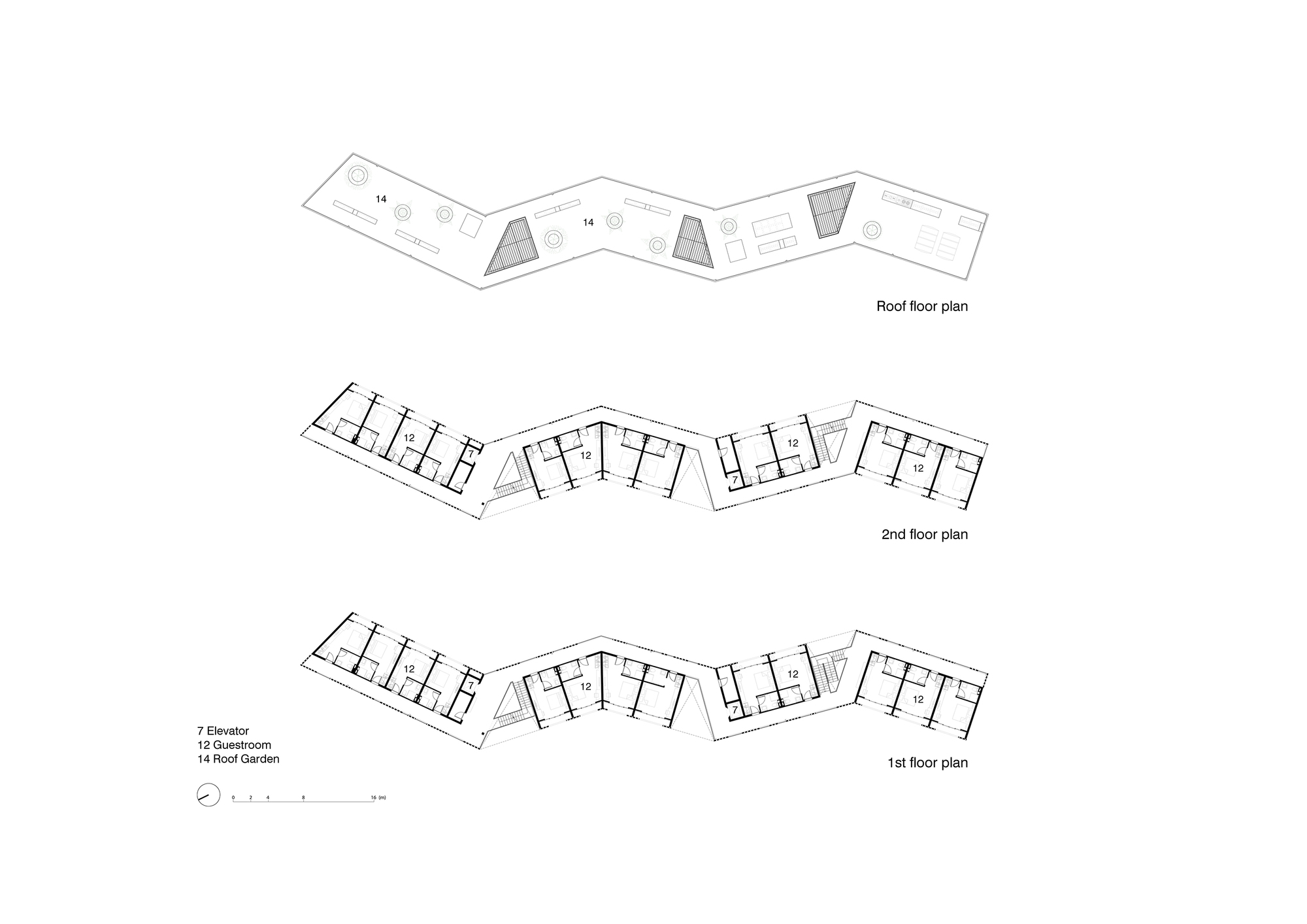

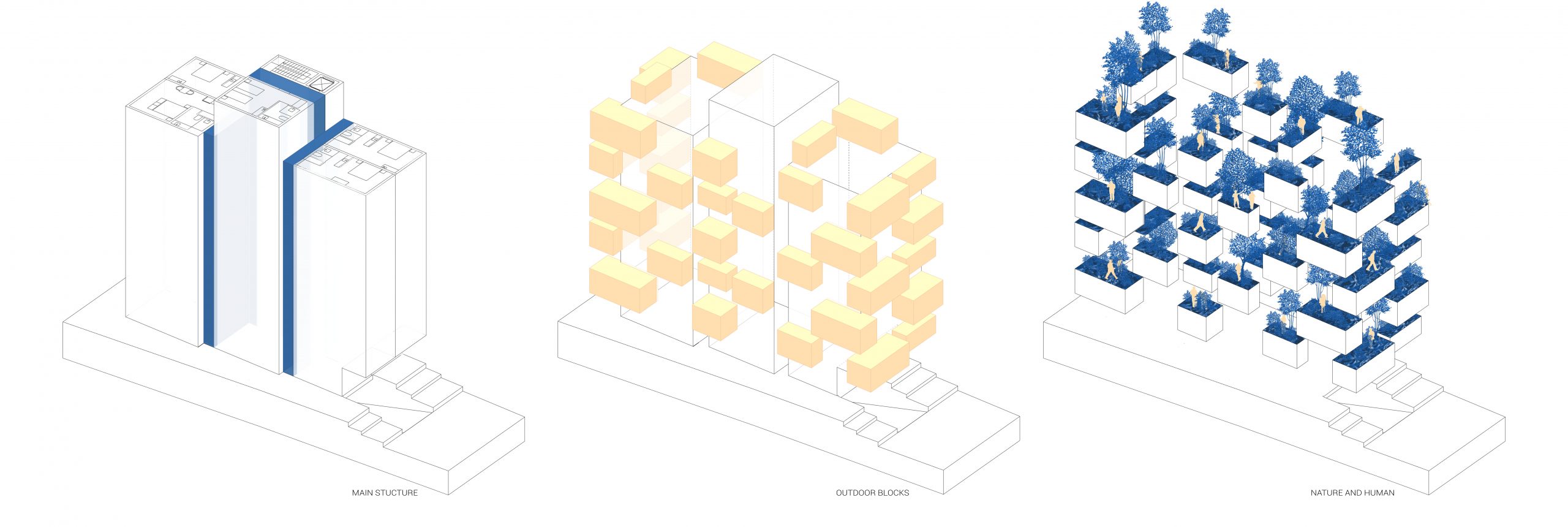

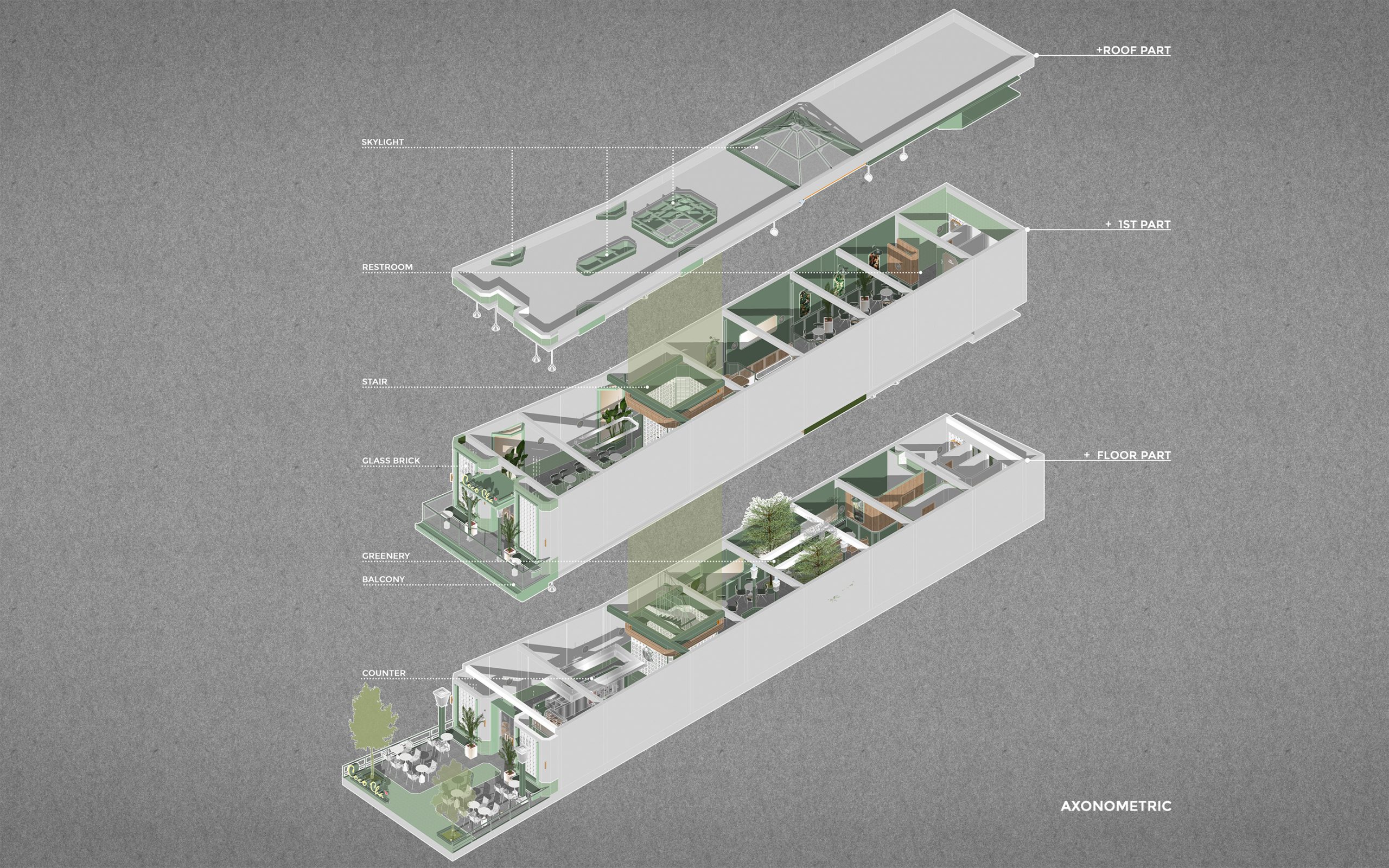

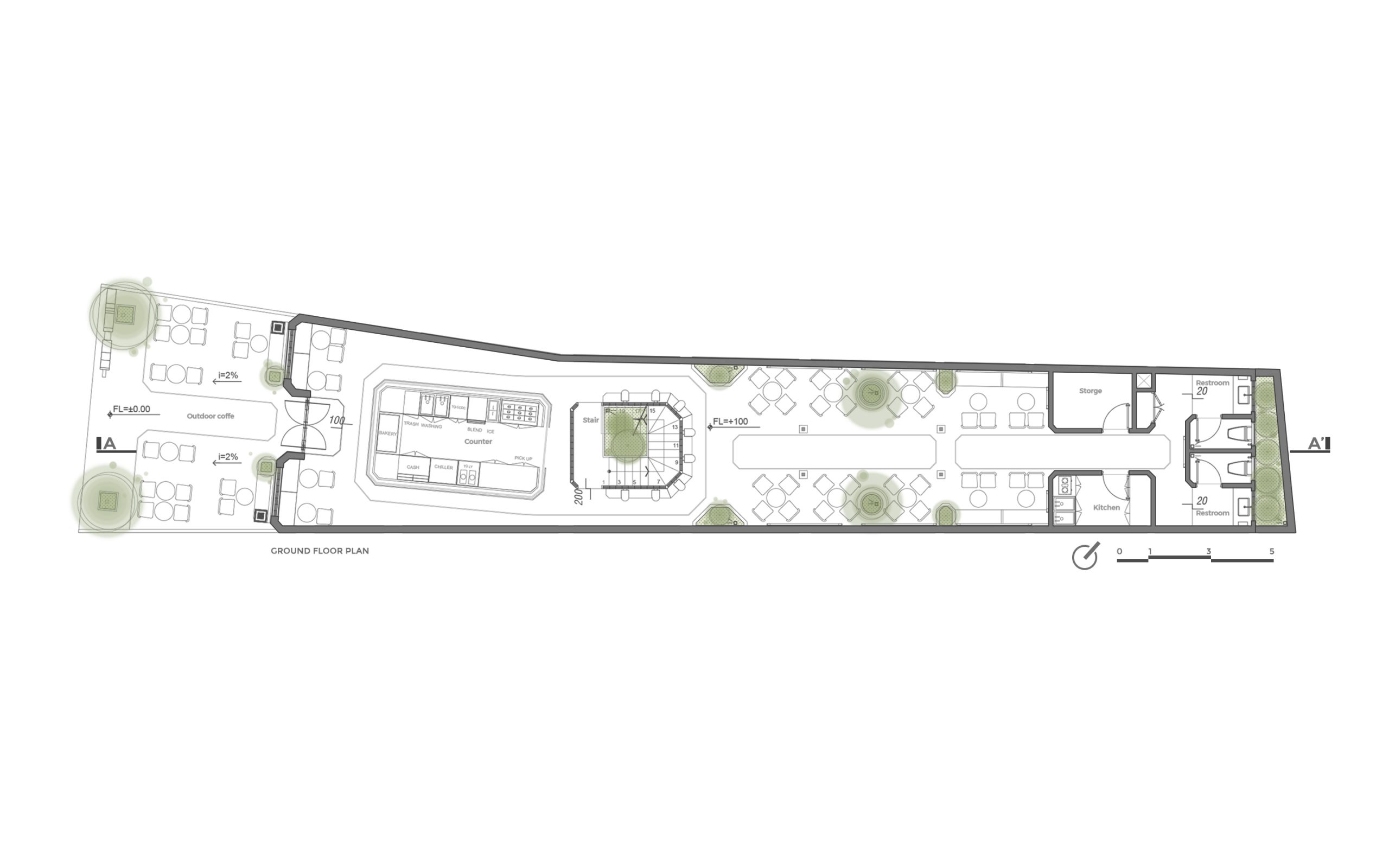

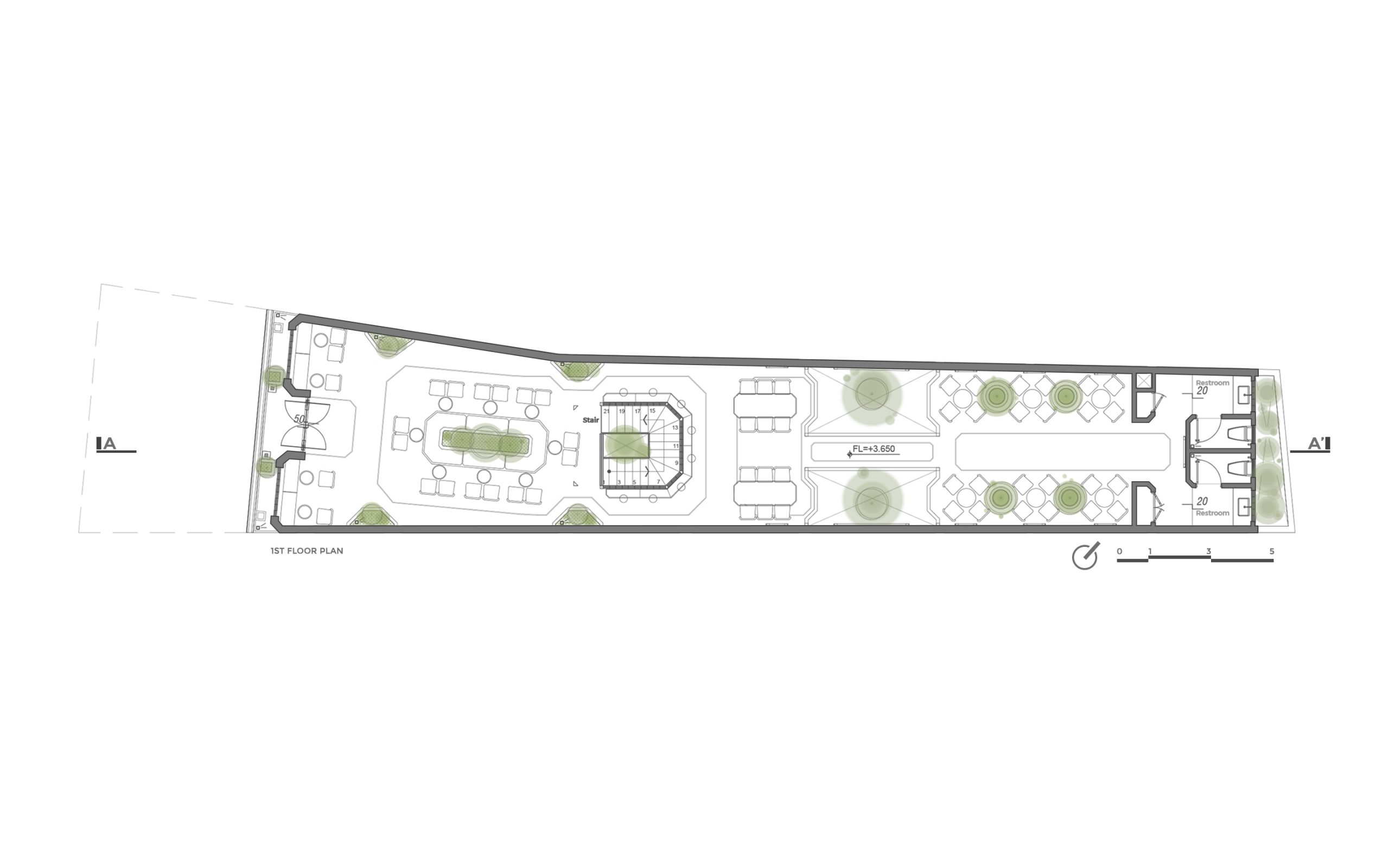

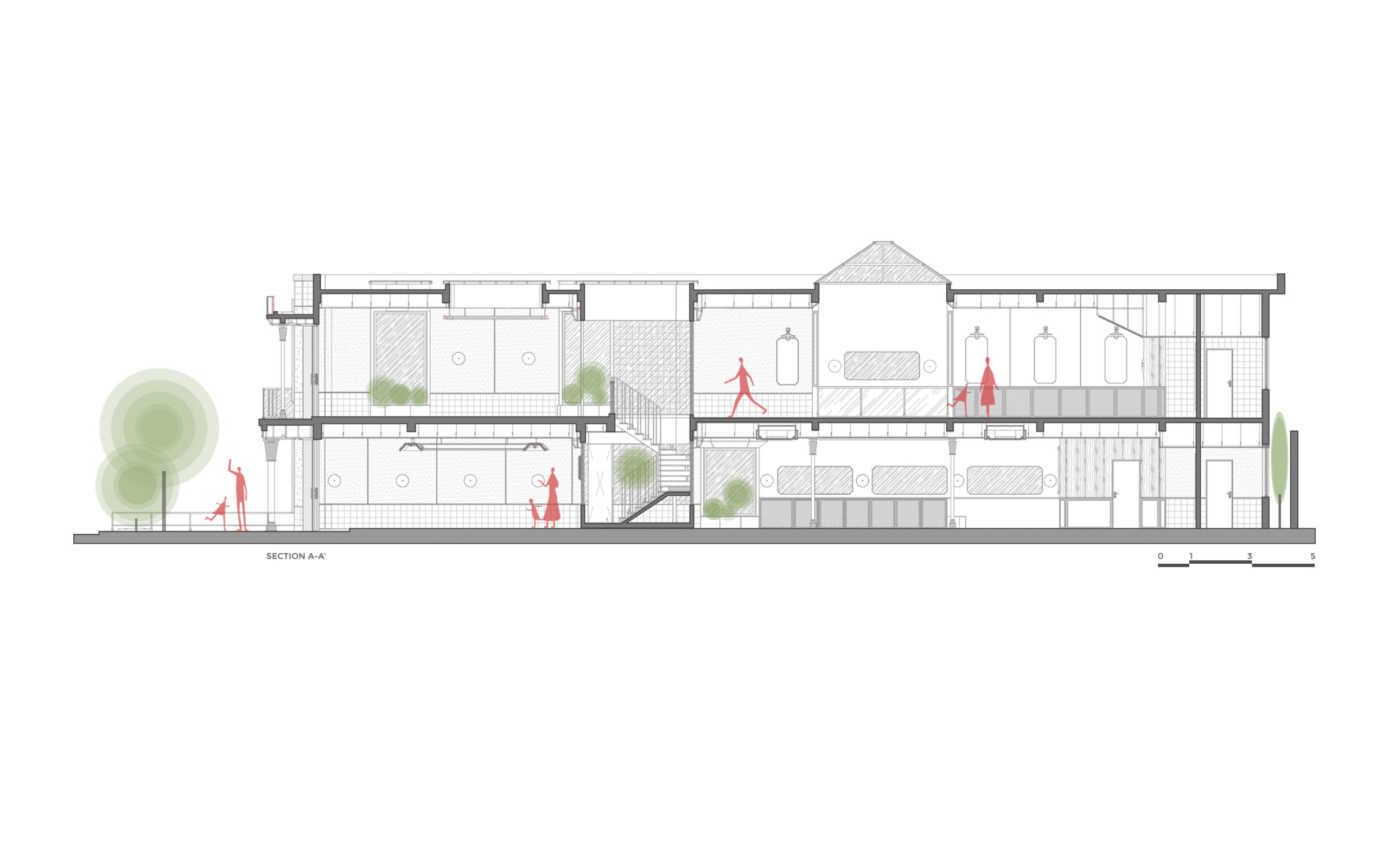

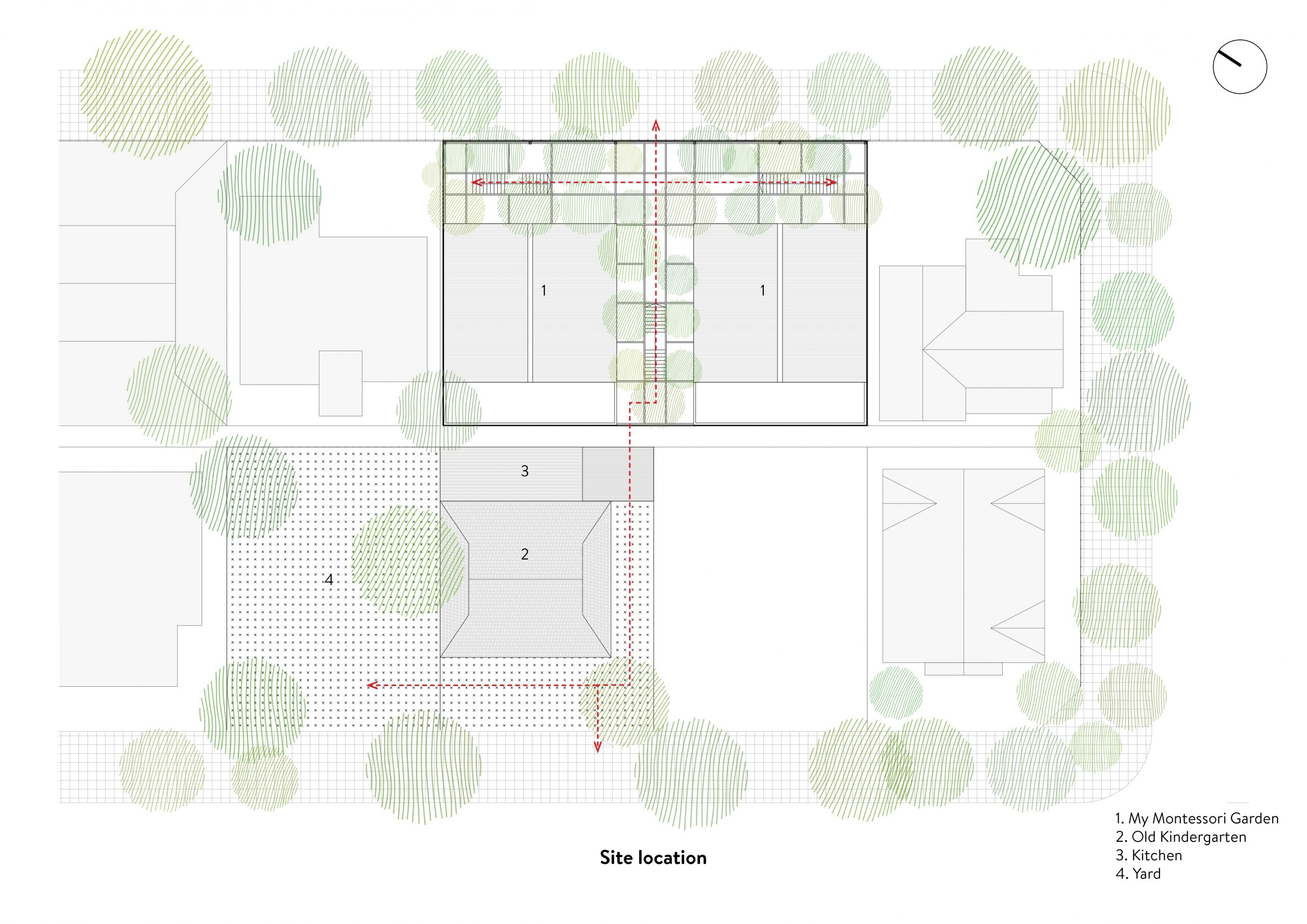

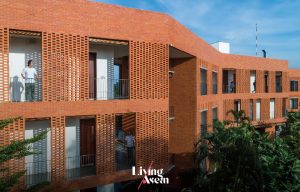

The brainchild of Full Scale Studio, a homegrown architectural practice, Proud Phu Fah Muang Chiang Mai embraces reconnections with the natural world. It consists of a pair of three-story buildings thoughtfully devised to merge into countryside vernacular, at the same time reaping the full health benefits of sunshine and fresh air.

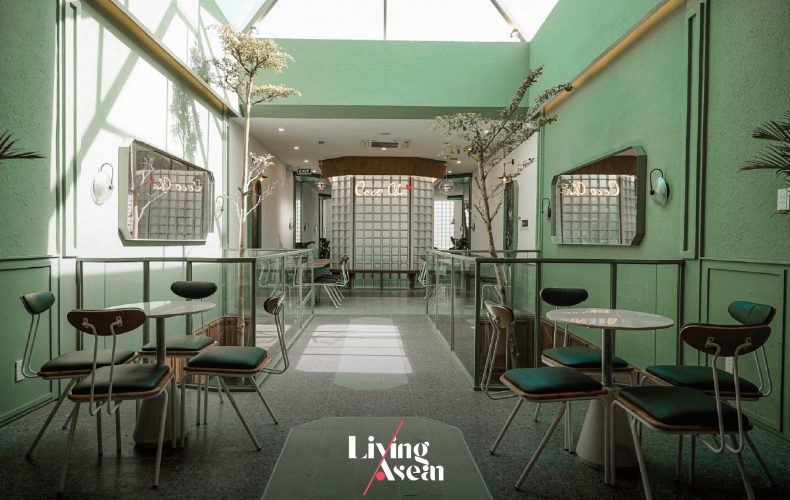

The main idea is to let the aroma of nature permeate through the landscape. Such is manifested in a pair of well-maintained giant rain trees providing shade and a focal point in the center courtyard. By design it has become a favorite place of relaxation and rejuvenation among hotel guests.

Front and center, well-thought-out planning ensures that all the rooms have access to the best view of the natural surroundings. The first building, called Building A, is directed at a 45-degree angle to soak up a wonderful panorama of the mountains, while the second, known as Building B, is set along the 90-degree line for a beautiful orchard view.

Where appropriate, new trees offering fragrant flowers are added to the existing contiguous woodlands, resulting in uniform composition.

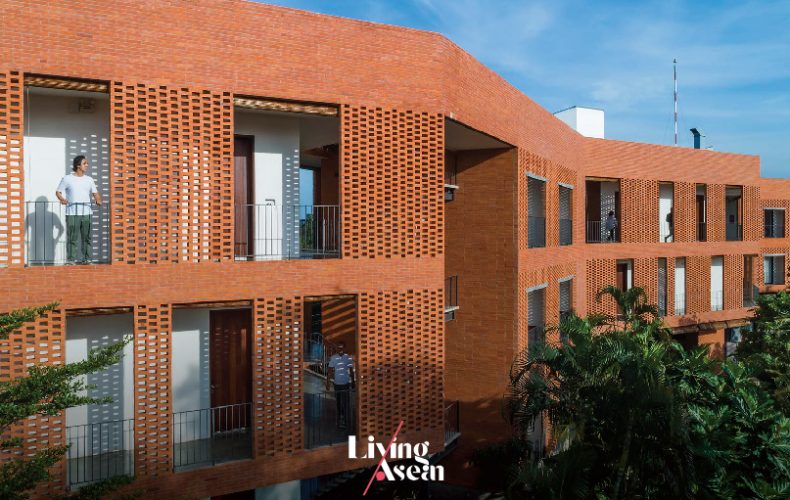

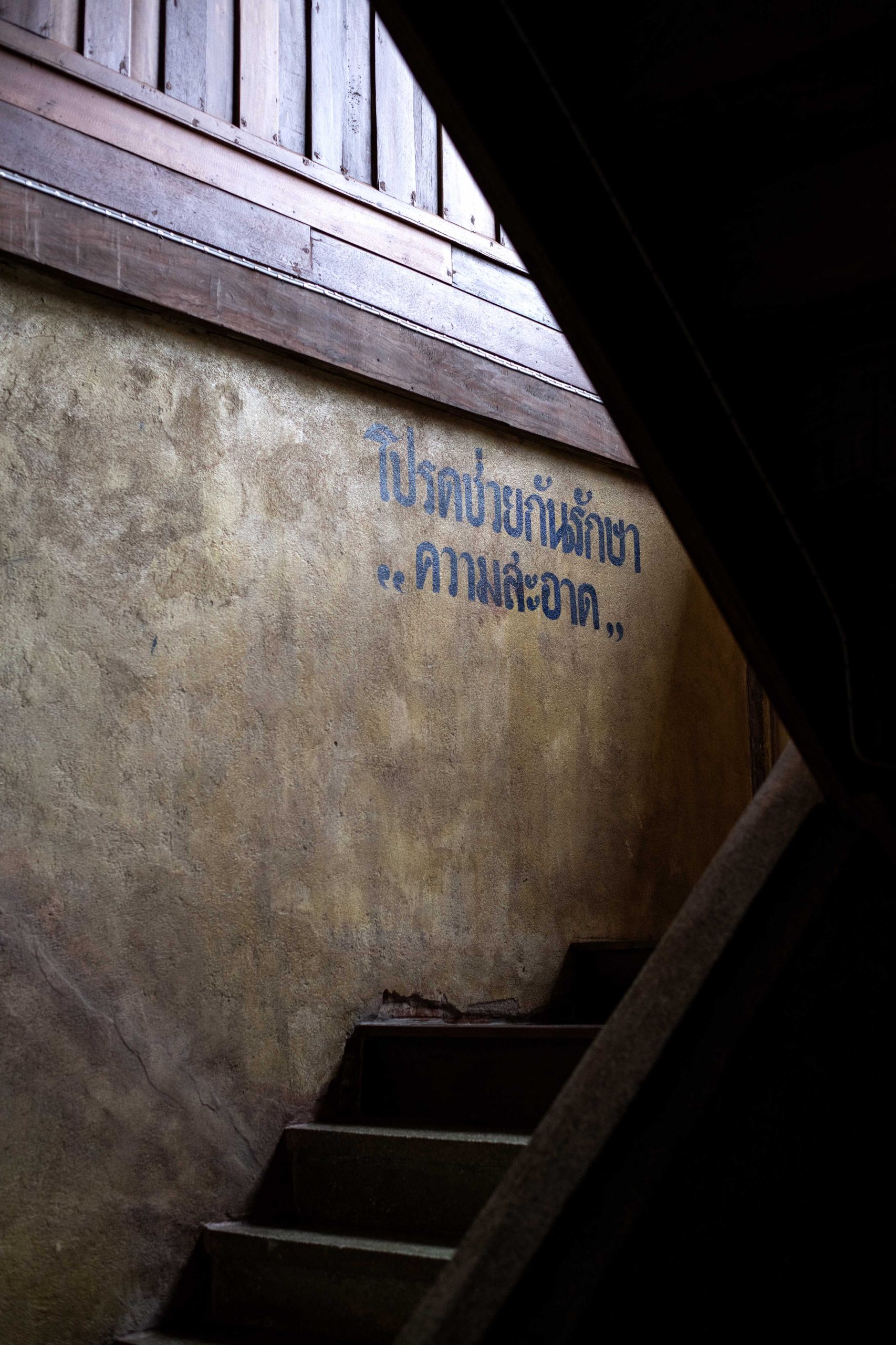

Architecturally speaking, it’s a project that emphasizes the use of concrete, brick and wood directly sourced from the locality as the building materials of choice. Aside from giving a sense of identity and cultural heritage, they double as storytelling tools conveying a great deal about the love of nature and preservation of traditional crafts.

An example of this is Minimal Lanna, a type of room that advocates Minimalism in art infused with a mix of traditional crafts and modern interior design.

The room has furniture beautifully crafted of teakwood, ceramic tiles, and ceramic washbasins with kid design custom-painted by the property owner, plus decorating items in a variety of finishes handcrafted by local artisans and contemporary artists in the region.

Overall, it’s a design that places great emphasis on the beauty of simplicity and the use of soft neutral tones for deep relaxation.

To reduce the harsh texture of concrete construction, red bricks come in handy for multiple applications. Among other things, the external envelope of Building B consists of brick walls inspired by the craft of basket-making known as “Lai Song” patterns in the vernacular of the Northern Region.

Like poetry in motion, the reflection of sunlight on the walls creates interesting sights and shadows that change from morning to evening.

For indoor thermal comfort, where appropriate perforate walls are built using contemporary cement blocks with holes in them that serve as engine driving natural air circulation and letting natural daylight stream into the interior.

In a way, they form an integral part that blends seamlessly with the landscape enlivened by the sounds of a babbling brook amid a forest garden with walkways made for relaxation. Together, they go to work connecting Proud Phu Fah Muang Chiang Mai with the idyllic natural setting.

Architect: Full Scale Studio, Tel. 08-9154-1758

Landscape Architect: H2O Design Co., Ltd, Tel. 08-1531-1871

You may also like…

The Ben Tre Hotel: A Brick Hotel amid Lush Orchards, Fresh Air and Sunshine

The Ben Tre Hotel: A Brick Hotel amid Lush Orchards, Fresh Air and Sunshine

The Pusayapuri Hotel: Redefining U-Thong Architecture from a Modern Perspective

The Pusayapuri Hotel: Redefining U-Thong Architecture from a Modern Perspective