/ Hanoi, Vietnam /

/ Story: Kor Lordkam / English version: Bob Pitakwong /

/ Photographs: Trieu Chien /

Greetings from Soc Son, a village near Hanoi that’s home to a museum nestled in an old orchard. Known as Đạo Mẫu Museum, it stands on 5,000 square meters (about an acre) of land surrounded by lush woodlands and rolling hills. In recent years, the area has attracted many travelers, thanks to beautiful scenery and unspoiled landscapes.

The Đạo Mẫu is a museum and a home in one. Xuan Hinh, the owner/artist who created it, lives on the project, which conveys a great deal about his unwavering commitment to preserving the architectural heritage and folk traditions unique to this part of the country.

Among them is the traditional veneration of deities of Vietnam’s folk religion that’s gradually disappearing from modern society.

By definition, the term Đạo Mẫu is Vietnamese for mother goddesses, or deities in folk religion treated with reverence and adoration since the dawn of time.

It’s part of the ancient Vietnamese belief system that seeks communications with supernatural beings, especially the goddesses or female deities and a fascinating aura of mystery that locals adhere to and observe in everyday life.

It’s not clearly understood how such belief systems came into being. Only that female deities were worshipped for thousands of years since the earliest times. This is especially true across Southeast Asia, where female divinity is mostly concerned with the life-giving and nurturing aspects of nature.

Understandably, the power of nature is personified as a woman symbolizing a creative and controlling force, and hence the term Mother Nature as we know it.

Long story short, it’s the line of thought mentioned above that inspired Xuan Hinh to join forces with ARB Architects, an architectural practice based in Hanoi, in creating an architectural masterpiece in this regard. It serves as a vehicle to express ideas about the preservation of the folk culture that’s rooted deeply in the belief systems about the force of Mother Nature.

The result of all this is a group of towering structures covered in vintage clay tiles reaching for the sky through the void of space among the fruit trees on the property. The idea is to avoid coming into contact with surrounding lush foliage and let nature permeate.

Philosophically, it’s a reflection on the importance of the need to live a conscious lifestyle and make the world a better place for all living things.

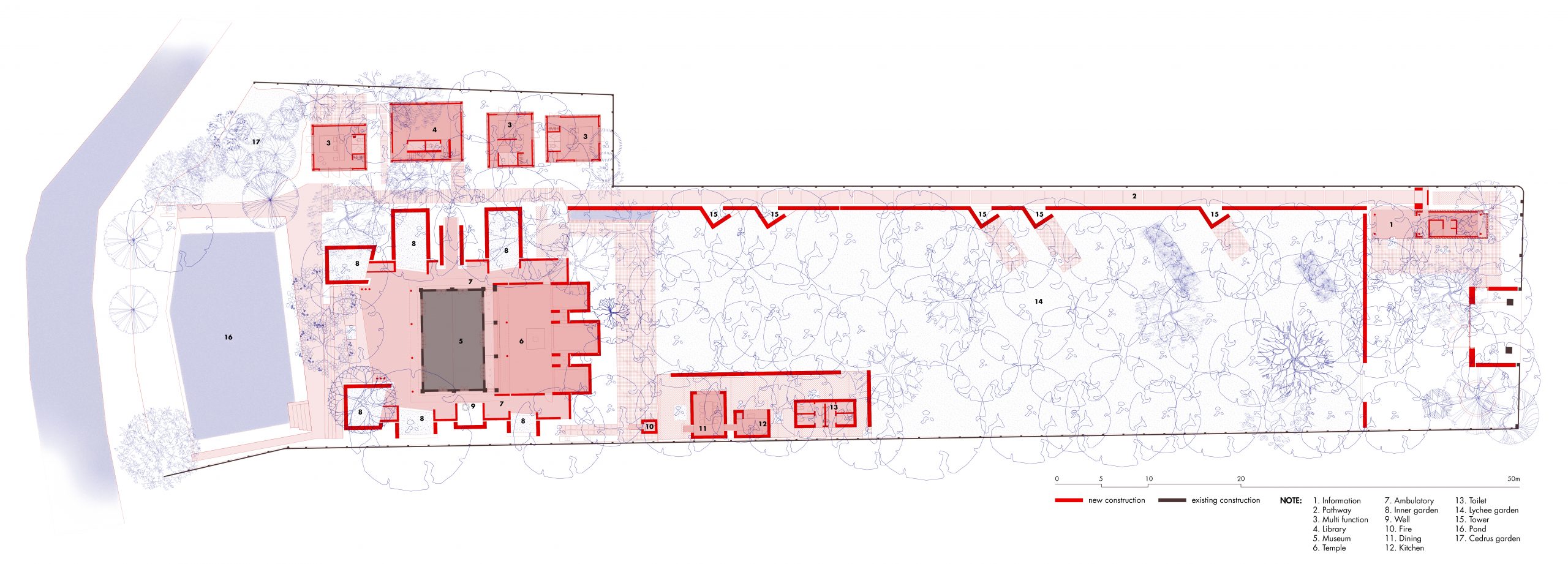

The Đạo Mẫu Museum has two parts. First, the welcome area is a long garden path that runs along the boundary wall marked with towering structures at intervals. There are five of them in all that serve as the focal points to get people’s attention.

The rustic garden path leads to the main area consisting of a place of residence and a museum at the rear of the property. There are service areas and smaller buildings nearby. The old house where the owner/artist lived previously now provides space for collectibles connected with the veneration of Đạo Mẫu, the female goddess.

Elsewhere, new buildings merge into the darkness of the fruit orchard. Or it can be said that the trees blend beautifully with the built environment. Either way, it looks the epitome of a perfect picture, in which all things in the universe are inextricably linked.

More so than anything else, every square inch of the towering structures and boundary walls is covered in vintage clay tiles in varying shades of earth tones. They are reclaimed construction materials that the owner/artist had kept in his collections over many years.

The tiles were recycled from much older homes across the Northern Region of Vietnam, more than one hundred of them in all. He collected them over time when the old homes were either renovated or dismantled as a result of the increasing globalization of the economy.

For Xuan Hinh and the design team of ARB Architects, the discarded objects are priceless works of art. They are man-made artifacts whose value cannot be determined, plus they provide a reflection on the ways of life of the people of Vietnam in times past.

It’s the opportunity to adapt them for a new use, thereby upcycling them into something of higher quality and value. And from the cultural perspective, it’s about showing respect for the past, celebrating the present and inspiring the future.

Owner: Xuan Hinh

Architect: ARB Architects (www.facebook.com/arb.architects)

You may also like…

The Elephant World of Surin: Architecture Dedicated to the Asian Pachyderm and the Kuy People

The Elephant World of Surin: Architecture Dedicated to the Asian Pachyderm and the Kuy People

Moonler Wood Furniture Adds a New Dimension to Chiang Mai Crafts

Moonler Wood Furniture Adds a New Dimension to Chiang Mai Crafts